“It is possible to fly without motors, but not without knowledge and skill.”

In my first blog of this series, I contrasted countries with high-road and low-road employment and skills systems. In the second, I examined the impact recent immigration has had on each of these systems.

Turning now to skills development, the primary measure of any national vocational education and training system is how well it succeeds in meeting the needs of the industries it serves. This might be quantitative – the number of newly trained recruits – or qualitative – the right range and level of knowledge and skill.

By this measure, ‘high-road’ construction industries such as those of Scandinavia, Benelux and German-speaking countries put to shame their ‘low-road’ peers, including the UK and most countries of central and eastern Europe. Like Wilbur Wright in the quotation above, the former group place more faith in the value of workforce knowledge and skills development than the latter.

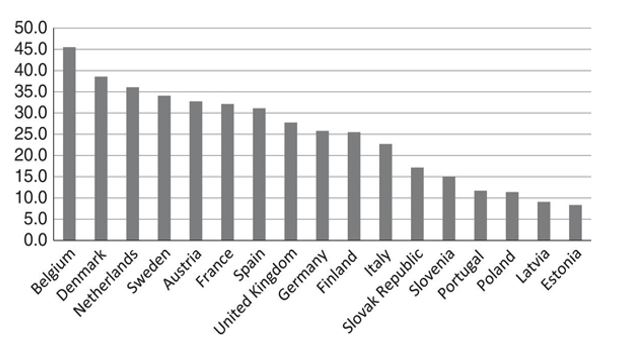

The table below shows there is also strong evidence to support a correlation between more and better training and stronger labour productivity performance.

Table: Added value per hour in construction. [i]

.png.aspx)

‘High-road’ systems do not arise as a result of chance, but from Governments empowering industry to establish and maintain robust training and competence standards. For example, when asked by a UK counterpart to explain his own country’s success, one Austrian minister explained: “We handed vocational education over to the social partners, then left them alone for 30 years.”

Often, in these countries, Governments reinforce the effectiveness of industry leadership through supportive public policy and regulatory measures. As well as widespread adoption of direct employment, these measures include giving universal effect to grading and training provisions in collective agreements and/or establishing mandatory occupational licensing regimes.

In the UK, construction skills development has never recovered from the strategic decision, rolled out between the 1970s and 1990s, to prioritize cost minimization above nearly all other considerations.

In the interests of lowering ‘barriers to entry,’ Governments, clients and the top tier of industry worked tirelessly for twenty years to undermine or remove regulations and institutions previously designed to support a higher road approach.

One result of this headlong sprint down the low road was a catastrophic collapse in construction apprentice recruitment, down from 112,000 in 1966 to 16,400 by 1985.

Many previously skilled activities were broken up and commodified into multiple, narrowly defined, low-level jobs. Germany, for example, currently recognises just 19 construction occupations, compared to around 150 recognised in the UK.

The fact that an individual does not work for them directly, or may leave after only a short time, is a major disincentive for installation businesses to invest in workforce training. This means, counter-intuitively, the lower the training requirement the less likely businesses are to invest in training – accelerating the downward spiral even further.

Table: Links between installer occupational level, employment status and apprentice recruitment

|

Occupation |

RQF level |

% direct employment (ONS 2018) |

No. apprentice starts (ONS 2019/20) |

|

Electrician |

3 |

70% |

5730 |

|

Plasterer/ dry-liner |

2 |

23% |

20 |

|

Roofer/ cladder |

2 |

24% |

10 |

Where does this leave the UK’s construction skills system – especially now that the immigration tap has been turned off and the predicted off-site ‘revolution’ has metamorphosed into something more akin to an evolution?

There is a lot at stake, as UK and devolved Governments all now rely heavily on construction businesses to help deliver key policy priorities – from transport and energy infrastructure, smart cities, net zero, building safety to the ill-defined, ‘levelling up’ agenda. The Skills Plan, published by the Construction Leadership Council, earlier this year is dizzying in the scale and range of the improvement aims it sets out.

My view is that real improvement will come only when the UK looks again at the historic choice between the low-road and high-road approaches. This needs a greater appreciation of other countries’ systems, the useful lessons from higher road sectors in the UK – including our own electrotechnical sector – and a willingness to address long-standing structural obstacles to sustainable skills development.

It is to one of biggest of these obstacles – the UK’s comparatively low employment standards – that I will turn in my next blog.

[i] Source: Arnholtz, J and Ibsen, C., ‘Sustaining High Road Employment Relations in Swedish and Danish Construction Industries’, in Belman, D, Druker, J and White, G (eds) (2021), Work and Labour Relations in the Construction Industry: An International Perspective, Routledge, London